Prospect and Refuge in Genoa and Naples

Why are we drawn to some buildings, repulsed by others? Feel comfortable in one house or city, on edge in another? A common starting point is taste- maybe we think we like sleek modern design, or the coziness of an old traditional house or neighborhood. But is it just a matter of taste? Even modernists are awed by Gothic cathedrals, and a building like Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater attracts people with a wide range of taste.

Grant Hildebrand, architect and architectural historian, thinks we should pay more attention to psychological and evolutionary factors in determining the emotional impact of buildings and cities. As I read his book, “Origins of Architectural Pleasure,” I noticed that it compellingly illuminated much of my attraction to two cities that I am particularly drawn to - Genoa and Naples. It even seemed to shed light on why I enjoyed exploring the cities in a certain way, which I illustrate below with pictures.

Prospect/Refuge

The most fundamental aspect of his theory is the idea of “refuge” and “prospect.” Refuges are places that provide shelter and safety - from the elements, and historically, predators. Compared to other animals, we have very limited physical defenses against the elements or attacks, and our childhood is long and comparatively helpless. We therefore developed a deep rooted desire for places that feel sheltered and safe.

However, the "prospect" was equally important - "a place where we can hunt and forage, a place that offers long views over long distances and is brightly lit". We not only need refuges and prospects, but we like to have them in a specific relationship to each other: we want to able to survey the open prospect from a safe and concealed refuge, to see without being seen. And if we are out in the open, we like to have a clear path of retreat to our refuge. Not only that, (we are quite picky) it’s also important to be able to control and vary the amount of prospect compared to refuge that we experience. At different times of day, in different moods, at different points in life, etc., we may desire more of one or the other, and individuals may have differing preferences. Hildebrand therefore argues that it is important to have ample forms of both prospect and refuge in any design.

A “cozy” place with a view seems to be one of the most common architectural desires - a modern expression of these unconscious needs for refuge and prospect?

Hillebrand makes a distinction between primary refuges and prospects - our immediate surroundings - and secondary ones that can be seen in the distance. For example, this photo is taken from what feels like a primary refuge, protected and enclosed by the overhanging tree. It looks out over an obvious prospect, but the town offers a secondary refuge within the landscape, nestled as it is between the hills. And you can anticipate the views you might have from the town - even the imagination of a new prospect is enticing.

Mystery

The second element of his theory is in essence mystery. We are drawn to things that are not fully revealed to us. He thinks that this curiosity about the unknown, while carrying its obvious risks, was beneficial evolutionarily. We’re drawn to find out what’s around the bend, especially if what we can see holds the promise of a rich landscape.

Complex Order

The third and final main element of the theory is that we are drawn to “complex order.” That is, we like complexity in a built environment, but not complete randomness - we like to be able to make some sense of the complexity, to notice patterns and mentally categorize different elements. We are drawn to complexity because complex environments are “probably rich in quantity and variety of resources; a simple surrounding is probably deficient.” But complexity can be overwhelming and disorienting if it is seemingly random, lacking any discernable way of categorizing or distinguishing parts of it.

A perfect example of this is the structural frame of a building. Tracy Kidder noticed this in his book, “House": “[The carpenters] can gaze at all they have accomplished. . . stopping a moment and looking at all they’ve added to the box of geometry that has grown out of the sand. A frame is nice to look at. Like a hammer or a bridge, it shows you how it works."

I think he implicitly makes the same point about the pleasure in making sense of a complex scene. It’s not that the framing literally “shows” us how it works. Instead, we can look at this complex wood structure and figure out how it works because the different components (walls, floor, roof, etc.) are easily distinguishable, and their relation to each other is intelligible. Framing is satisfying to look at because it’s like a three dimensional puzzle that we can easily solve.

Getting back to Genoa and Naples, these cities are exciting and enjoyable to be in because they combine these three elements of architectural pleasure:

They are composed of millions of prospects and refuges, in varied forms, all throughout the city. Unlike American cities which can often feel like giant prospects, vulnerable and exposed - surrounded by tall, looming buildings, on wide streets dominated by cars - Genoa and Naples combine prospect and refuge on nearly every block. They are composed of mostly small, often winding streets, interspersed with plazas, courtyards, and lookouts. This variety, along with with streets and buildings of a human scale, allow you to experience both enclosure and openness, and easily switch between them.

They are highly complex, both in terms of city layout (they could be considered the opposite of a grid) and architecture, yet not without forms of order. I have heard Genoa described as a wedding cake because it seems to be built in cascading layers. As you spend time walking around, you slowly begin to experience these loose patterns,.

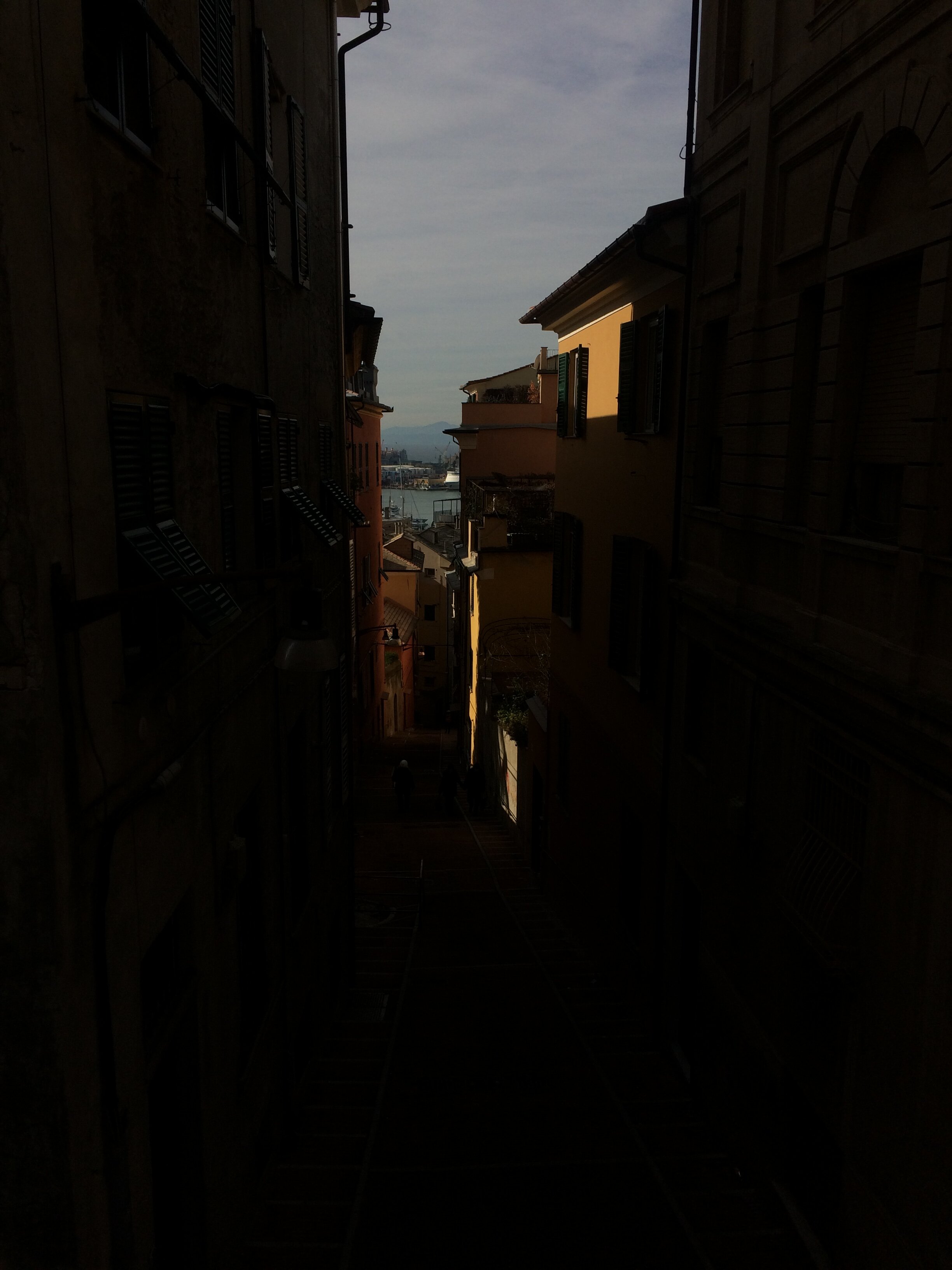

Mystery… Because of the design factors described above, walking through these cities is exciting. The winding, narrow streets, changes in elevation, and non-standardized layout constantly entice you to explore new areas by providing small glimpses of what they might offer.

Here are a series of photos taken in more or less chronological order as I explored each city. The path I took seems to make sense based on this theory.

After arriving in the center, I would spot a high point and begin to make my way there.

Genoa

Naples

Genoa

Naples

From up high, I could not only get oriented but also get a sense of the scale of the city. I think the urge to escape the claustrophobia of the city by getting above it is somewhat universal. It feels good to make a rough mental map of the landscape and have some sense of how we fit into it (making order out of the complexity, in other words). Knowing, for example, if it will take roughly an hour or a day to get from one side to the other, or where you might be able to get a broad view again, completely changes the experience of being in the city. While this kind of mental map can be developed over time in a place where it is not possible to get a bird’s eye view, it does not have the same visceral quality.

Sometimes when I would get to the high point I had initially aimed at, I saw a further, higher point in the distance, an even more promising lookout. Sometimes I would continue up, sometimes not. It can be nice to leave something for the future.

Hildebrand writes about a small seaside town in France: “The town’s narrow streets and the solidity of their surfaces suggest refuge; the shelter they offer from the sea is palpable…” I think that can be felt in the photo below of Genoa - a refuge from the mountains above and the sea below.

This feeling of the city as a refuge becomes more pronounced as it gets dark and the city appears as a cluster of lights. This seems like an obvious observation but I think there are two slightly distinct reasons for this feeling. One is our desire to move from dark places to well-lit ones for reasons of safety. The second is that lights signify people. Hildebrand talks about how subtle imprints of human activity - a stone staircase that is heavily worn in the middle, for example - tell us that others have been there before, and that it is likely safe. I think the sight of far off lights - especially when we are in uninhabited areas- gives us a similar feeling of comfort - to know that there are people there, and that we can make our way to a refuge.

As I made my way back down into the city, I slowly experienced the transition from prospect to refuge. The paths gradually become narrower, and I felt like I was becoming enclosed and enveloped within the city - a feeling of safety from exposure.

Genoa

There was also an excitement in knowing roughly what lies below, but none of the specifics, and taking a plunge into the city. I would lose sight of whatever I had managed to see from above, and choose from a vast array of narrow staircases, alleys, and streets to make my way down to the center and ultimately the water.

Naples

As I descended, I periodically emerged from the narrow streets to wider open spaces. This created a very satisfying combination of enclosure and openness, and of anticipation followed by periodic reveals. Being able to see where I came from and where I was going contributed to the “mental mapping” of the city.

An opening between “layers” of Genoa with some kind of farm in the middle of a U-shaped street.

Finally, I as I reached the center of the old city, the feeling of enclosure became more pronounced as the streets narrowed further (many streets in Genoa are only five or so feet wide) and less light reached the ground level.

Genoa

Walking here is almost incomparable with walking in an American city. Again, it’s obvious, but the streets actually feel like they are built for people and walking. The blogger Nathan Lewis has some insightful observations about what makes a street feel this way (narrowness and a lack of tall sidewalks and “roadway segregation” are key). One might think that it is the age of the buildings and streets in Naples and Genoa that give them these qualities, but he makes a convincing argument that it has less to do with age and style than street width, building height, and setback distance.

Naples

In the language of prospect-refuge, the center of the city feels like a refuge from the outer world - it is hushed, dark, and enclosed. Yet, this could be too overwhelming if it were not broken up by small prospects, like these courtyards.

Exploring the center is an intense, sometimes even overwhelming experience. One additional aspect of Hildebrand’s theory is peril. He says that danger in the built environment - if adequately controlled- can be attractive and exciting. The darkness and emptiness of some parts of these centers adds a tinge of unease that contributes to the feeling of mystery.

Genoa

In some sense, the old centers do not feel like refuges because you do not have a clear view of your surroundings - you can’t see a broad area around you without being seen. They can feel both claustrophobic and exposed at the same time. The feeling in these places doesn’t quite fit the description of either prospect or refuge, but it is an enjoyable kind of tension. This illustrates that we do not always need to feel all of the elements of “architectural pleasure” to enjoy the experience of a place - or maybe more accurately, that we can derive different kinds of pleasure from different elements. Hildebrand stresses that If we control the period of time we spend in a place and how we move through it, places that are “off” in some way can be very satisfying to explore.

The conceptual elements are not specific in any way to Genoa or Naples, but these cities offer them in unique and beautiful forms. It’s worth thinking about how the various elements that give these cities so much “architectural pleasure” could inspire design in other places and contexts. It’s not a new thought - in fact, in the 1960s the architect Franz di Salvo took direct inspiration from the narrow streets of Naples’ historical center to design the “Sail” shaped public housing projects in the outskirts of the city. Sadly, the buildings are a fascinating study in how capitalism can corrupt the best of design ideas. The area became a center of drug trafficking and organized crime, dramatized in the movie and TV series “Gomorrah,” and many residents hated the buildings and considered them oppressive, not just for their state of disrepair but also their feeling.

The story of how things went wrong is long and complex, but one aspect is particularly connected to the subject here - the importance of details.

The image below shows the architect’s intention on the left and what was actually built on the right. Key details were completely transformed and disfigured to cut costs. The differences demonstrate the effect of changes in materials, lighting, and scale on how a building or environment feels.

The walkways between buildings were meant to be steel and the buildings were to be set far enough apart to allow light in. Instead, the buildings were jammed together and built entirely out of concrete. These changes created a dark and imposing environment. Despite theoretically sharing some characteristics of Naples’ alleys and small streets, the buildings failed to capture the desired feelings of its environment. Of course, it wasn’t just the architecture that was lacking, and even if it had been built correctly it would not have escaped the problems of economic underdevelopment. Often the problems of public housing projects are blamed on the architecture, which has never made sense to me. The design obviously plays some role, but it’s a fantasy to think that design alone could solve structural economic problems. This shouldn’t degrade the importance of design or the analysis of its universal principles by people like Hildebrand. In a sense, this is a more hopeful view of the future of modern design: its real potential can only be achieved in a society with an economic basis for it.